I didn’t expect to hear the truth from someone who’d spent ten years working on the streets of Montmartre. She was sitting across from me in a quiet café near Place des Fêtes, sipping black coffee, no sugar. "I didn’t choose this," she said. "I chose survival." That moment changed everything I thought I knew about people who do this work. It wasn’t about glamour, or exploitation, or even desperation in the way the media paints it. It was about choices made in silence, under pressure, with no safety net.

Some of the women I met had been lured by promises of modeling jobs. Others were students who needed rent money after their scholarships vanished. One woman told me she started after her husband left and the child support never came. These aren’t outliers-they’re the quiet majority. And yes, some of them found their first clients through sites like escort pariis, not because they wanted to be part of a service industry, but because it was the fastest way to get paid without a bank account or references.

They Didn’t Wake Up One Day and Decide to Be an Escort Girl Paris

There’s no single path. No red carpet. No audition. For most, it begins with a crisis: a medical bill, a broken lease, a visa running out. I met a woman from Senegal who arrived in Paris on a tourist visa. She spoke no French. Her cousin told her about a job cleaning apartments. When she got there, the owner offered her double the pay if she stayed overnight. She said yes. That was her first night. She didn’t call herself a sex worker for months. She called herself "a friend who stays late."

Another woman, a former ballet dancer from Lyon, lost her leg in a car accident at 24. She couldn’t perform anymore. The government pension barely covered her medication. She started doing private sessions from her apartment. She posted on forums. She learned how to screen clients. She kept her account name simple: "Lily, 27, Paris." No photos. No videos. Just words. She told me she liked it because she could control the time, the price, and who walked through her door. "I still dance," she said. "I just don’t wear tights anymore."

The Myth of the "Escor Girl Paris"

There’s a version of this story that circulates online-the glamorous, high-end escort girl pariq who drives a BMW and wears designer clothes. It’s a fantasy. And it’s not just misleading-it’s dangerous. It makes people think this work is easy money. It makes people think anyone can do it if they’re pretty enough. The truth? Most women who do this work live paycheck to paycheck. Many sleep in hostels. Many carry a phone with two SIM cards-one for family, one for work. Many never tell their parents.

There’s a reason the word "escort" is used so loosely. It sounds safer than "prostitute." It sounds more respectable than "street worker." But it’s still the same work. The same risks. The same stigma. The same fear of being found out. I asked one woman why she didn’t switch careers. She laughed. "You think anyone hires a woman who used to be an escor girl paris for a job at a bank?"

The Hidden Infrastructure

Behind every client, every transaction, there’s a hidden network. Not always pimps. Not always gangs. Often, it’s just other women. A group chat. A shared list of bad clients. A WhatsApp group where someone says, "Don’t go to the hotel on Rue de la Roquette. He’s recording." Someone else replies, "I did. He tried to steal my phone. I ran. I didn’t tell the police. They’d ask me why I was there in the first place."

There are also women who run small, informal agencies. One I met called herself a "hostess coordinator." She didn’t take a cut. She didn’t control schedules. She just made sure new girls had a safe place to sleep, a clean towel, and someone to call if things went wrong. She had a spreadsheet. Names. Locations. Notes. "I don’t make money off them," she told me. "I just don’t want them to disappear."

Why Nobody Talks About This Until It’s Too Late

There’s a silence that surrounds this work. Not because the women are ashamed-but because the world doesn’t want to listen. Social services don’t know how to help. The police don’t trust them. Employers won’t hire them. Even other women in the same city won’t speak to them. I met a woman who’d been working for seven years. She finally saved enough to go back to school. She enrolled in a psychology program. She changed her name. She wore glasses. She sat in the back row. No one knew. Then one day, a classmate recognized her from a photo on a website. The next week, she dropped out. "I didn’t want to be a story," she said. "I just wanted to learn."

What Nobody Tells You About Leaving

Getting out isn’t a straight line. It’s not a movie scene where someone walks away and everything gets better. It’s messy. It’s slow. It’s full of setbacks. One woman I spoke with left after five years. She got a job at a bookstore. She lasted three months. She was fired because her boss found out where she’d lived before. She went back to work for six more months to pay off the debt she’d accrued during her break. She finally left for good when she got a scholarship to study nursing in Marseille. She still doesn’t tell anyone she was an escort girl pariq.

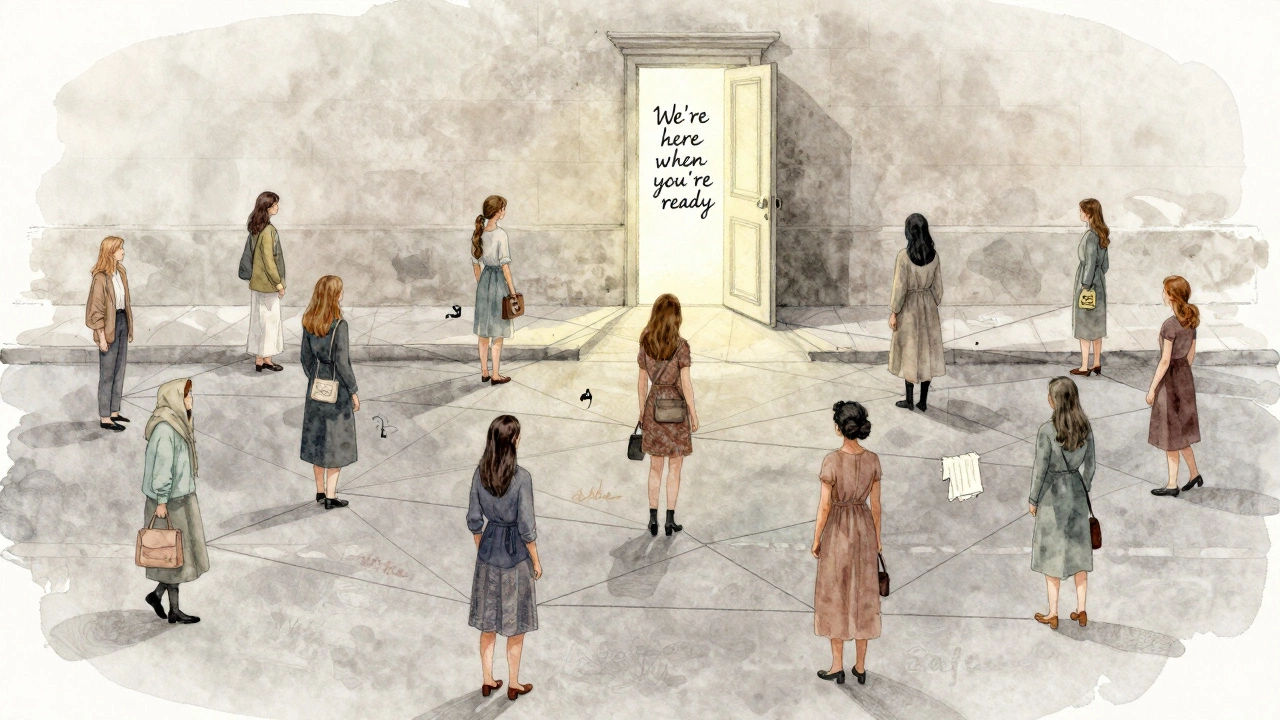

There are organizations that help. Some are run by former workers. Some are funded by NGOs. But they’re under-resourced. And they don’t advertise. You won’t find them on Google unless you already know what to search for. One group in the 18th arrondissement offers free legal advice, counseling, and help with ID documents. They don’t ask questions. They don’t judge. They just say, "We’re here when you’re ready."

The Moment I Knew

I used to think these stories were about morality. About right and wrong. About choices made in darkness. But I was wrong. These stories aren’t about sex. They’re about dignity. About being seen. About being allowed to exist without being labeled. The woman I met that day in Montmartre didn’t want my sympathy. She didn’t want my pity. She wanted me to understand that she was still a person. That she still laughed. That she still missed her sister’s birthday. That she still dreamed of opening a café one day. She just hadn’t gotten there yet.

That’s the moment I knew. Not because of what she did. But because of who she was. And how hard she fought to keep being her.